Sabias que hay agricultura en Galapagos? Es urgente que visibilicemos los roles de los agricultores para la conservación.

Agricultura para la Conservación en Galápagos

Eco-Experience Ecuador: Adventure and Ancestral Knowledge

Situaciones de conmoción social: extractivismo y la sociedad civil

Justice and organizing at Standing Rock

You are beautiful. You are a planet.

Adaptándose al Antropoceno en Galápagos

We want cities designed for people, not cars!

Cities often try to accommodate the relentless increase of cars on the road by widening roads and prioritizing cars over pedestrians or bikes. However, this is a miserable deal for everyone living in a city designed for cars instead of for people. Hostility, stress, and pollution are but some of the side effects of a car traffic jam.

570,000 firmas para consulta popular y salvar el Yasuní-ITT

Extractive activities valuation and alternatives (Part II)

The form of production is still being defined by the primary products that we export, some are mineral resources, others are oil or other primary resources, but there is no change in the raw materials-exporting modality of this extractivism, and neither is our submissive form of insertion in the international market being questioned.” - Alberto Acosta

After and before large-scale mining

How should the costs of extractive activities be quantified?

Assigning a price tag to the environmental damage is much harder than simply estimating the cost of cleaning up any spills or refill the kilometer-wide craters that would result from extractive activities. Just to give you an idea of how unrealistic any remediation plans are, Ecuacorriente, the local branch of the Canadian mining giant, has pledged a laughable 2.5 million dollars per year to rehabilitate the Mirador project area in Ecuador. This is outrageous considering the track record of mining rehabilitation: not a single mine has been adequately rehabilitated, not even in Canada. Not that any amount of money and effort is capable of putting back together an ecosystem that took millions of years to evolve, or truly compensate for people’s lives once they have been destroyed, but even if companies are legally obliged to provide proper compensation for damages, they might still not comply. This is the case of Texaco, now owned by Chevron. In Feb 2011, the oil giant was found guilty of dumping billions of gallons of toxic water throughout an area the size of Rhode Island. Chevron is legally required to pay 18 billion USD in compensation for their negligence, which decimated five indigenous communities and caused an outbreak of cancer and other oil-related diseases, threatening thousands of lives and permanently polluting their water supply and surrounding ecosystems. However, Chervon has no intention of recognizing this debt to the Ecuadorian people.

What are some direct and indirect values of natural areas?

Table 1: Utilitarian Values of Biodiversity. From "Why is Biodiversity Important" (NCEP 2003)

Just because something doesn't have a price tag doesn't mean it has no value. Only a few (direct) values have been included in the human economy, and we have barely been capable of valuing anything which is not extracted from the enviromnent (Table 1). One way to begin to wrap our minds around the dilemma of valuing nature is through the tools of ecological economics. We can explore the value of healthy ecosystems by identifying the priceless ecosystem services they provide and imagining how much it would cost (if possible) to replace them. Although there are alternatives to extractivism, the monstrous scale and infrastructure supporting the fossil-fuel industry makes it difficult to envision an alternative. Nevertheless, the value of the services that these ecosystems provide to our lives and industries is no less real. These values can and should be included into the human economy. Rather than placing our bets on industries that are certain to reduce or eliminate these benefits altogether, we could develop infrastructure to quickly identify, quantify, and maximize their value, so as to include them in the human economy. This way all Ecuadorians, nay, Earthlings (and not just those who own these industries) can "profit" from them. Below are some of the most basic, and therefore economically important functions of natural areas.

Watershed maintenance The paramos (see map above) are high-altitude grasslands whose soils act like a sponge and filter of water rushing down from the Andean mountaintops. These areas are a reservoir for lower watershed areas. They provide a useful and constant flow of filtered, low-sediment water to all the cities, industries and ecosystems that depend on them. No man-made reservoir and water treatment plant could ever provide the volume and quality of water provided by the paramos and their rivers, much less for free.

Genetic reservoirs:86% of earth's species remain unknown. It has been estimated that there are between 250,000 and 300,000 species of flowering plants, of which only about 10% have ever been evaluated for their medicinal or agricultural potential. Rainforests in particular are known to have a higher chemical diversity (a side effect of being an evolutionarily highly competitive environment) than temperate forests, for example. The applications of what we have yet to discover from biodiversity are endless: agriculture, alternative fuels, medicines, alternative materials, as an inspiration for industrial, mechanical, architectural design, etc. As Paul Stamets said, considering that fungi have been found to be able to break down components from biological weapons, conserving forests should be a matter of national security.

Supporting food independence: The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that about 75% of the genetic diversity of agricultural crops has been lost in the last century due to the widespread abandonment of genetically diverse traditional crops in favour of genetically uniform modern crop varieties. In fact, three quarters of global food production is comprised by just 12 crops and five animal species. Genetic diversity is necessary for successfully adapting to changing conditions like pests, disease, and climate change. Healthy ecosystems are necessary to support pollinator and pest predator populations, as well as keep weeds in check. Without pollinators and pest predators, people have to pollinate crops by hand and use hazardous chemicals which are detrimental to the ecosystem as well as for both farmer and consumer. The costs keep adding up.

Human health: Besides the health benefits of food, water, and shelter, biodiversity is a safeguard for human health, as both our physical and psychological health depend on on it. Medicinal components come from life (plants, fungi, microorganisms, and animals) and they need to be discovered before we can make a synthetic version. For example, roughly 119 pure chemical substances extracted from some 90 species of higher plants are used in pharmaceuticals around the world. Similarly, various mushroom species possess potent anti-microbial properties and antiviral activity against hepatitis B, herpes simplex, HIV, influenza, pox, and tobacco mosaic virus. Furthermore, some of todays most potent anticancerigenic medicines come from fungi. Studies have shown that our cognitive abilities are also greatly improved by exposure to nature and even that exposure to nature helps speed up recovery times for patients.

Pollination, integrated pest management, carbon sequestration, oxygen production, nutrient cycling, water cycling, and climate stabilization are but some of the invaluable environmental services provided by natural areas. But if the benefits of focusing our economic activities away from extractivism don't convince you, the costs business as usual with them surely will. As Bill McKibben points out in his fantastic Rolling Stone article, "We have five times as much oil and coal and gas on the books as climate scientists think is safe to burn. We'd have to keep 80 percent of those reserves locked away underground to avoid [a temperature increase of about six degrees celsius]". After all, climatic instability is costly at every level, and creating an Earth unsuitable for human life is, to say the least, antieconomic.

Table 1 source: Laverty MF, Sterling EJ, Johnson EA, 2003. Why is Biodiversity Important? Network of Conservation Educators and Practitioners (NCEP). Center for Biodiversity and Conservation of the American Museum of Natural History.

Water, Life, and the Dignity of the People (Part I)

This is one of the chants from the plurinational marches currently taking place in Ecuador. Thousands of Ecuadorians have been traveling 700 kilometers by foot across the Andes en route to Quito. The protesters are getting people to reflect upon an economic model that prioritizes the extraction of non-renewable resources over the defense of water resources, agriculture, food sovereignty, indigenous rights, and the conservation of biodiversity. President Correa is willing to sacrifice all of the latter for mining and oil drilling permits within designated protected areas, including one of the most biodiverse place on Earth, to pay for development initiatives in the country as a whole.

Ecuador’s 2008 constitution was internationally celebrated as the first in history to enshrine the rights of nature, as well as the Quechua concept of sumac kawsay, or “living well”. Paradoxically, the first approved legislation under the new constitution was the new mining law, paving the way for large-scale mining as early as January 2009. By March 2009, the national indigenous organization CONAIE had filed a petition challenging the constitutionality of the new mining law. Several communities in the province of Azuay whose water supply would be affected by the expansion of mining activities had also filed their case by the end of the same month. Three years later, neither case has even been heard by a judge.

Over 30,000 people flood the street to protest the expansion of mining activities and defend their right to a clean water supply in Azuay, Ecuador

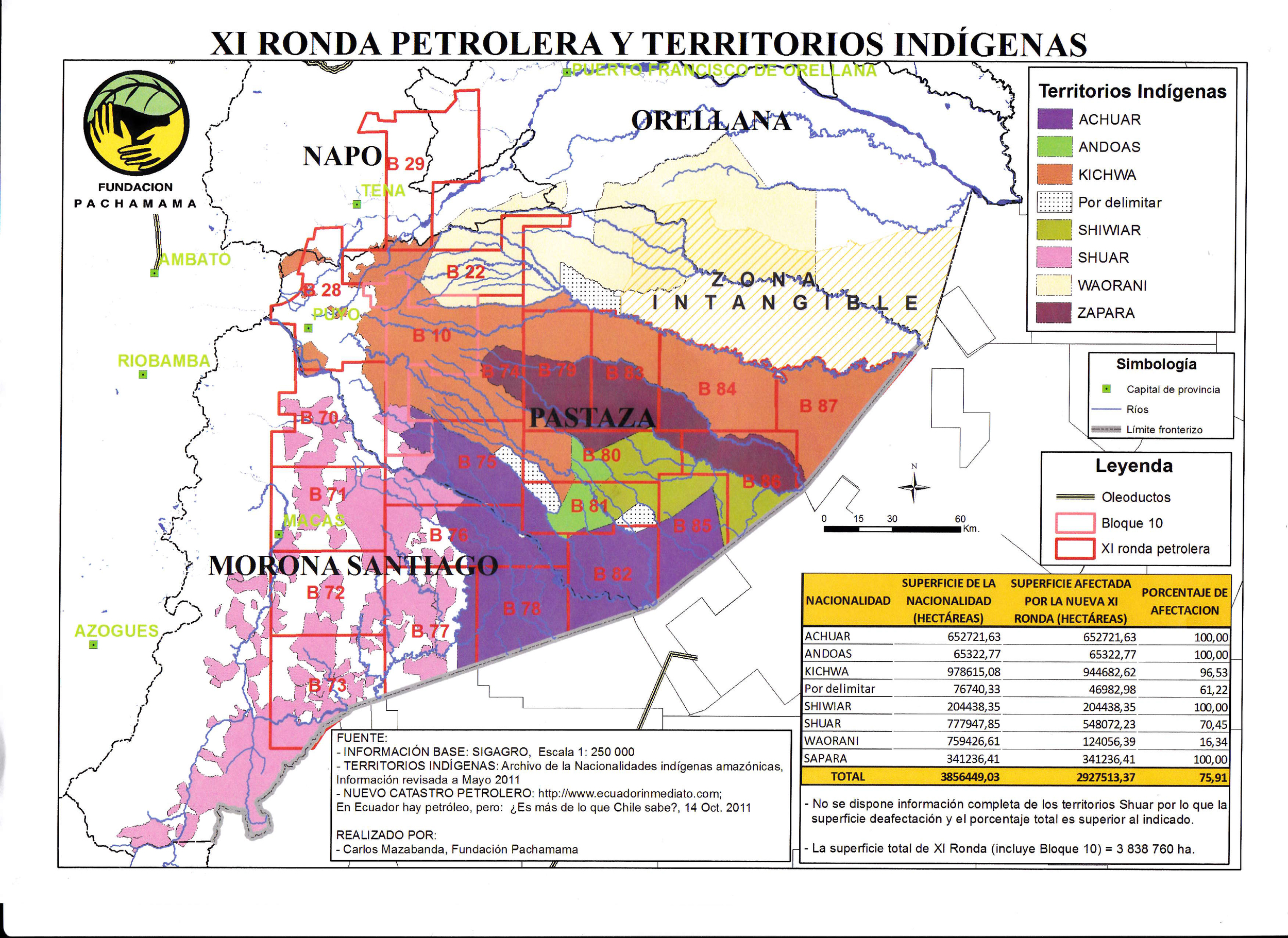

The president has dismissed the ongoing protests by indigenous and environmental groups as “infantile”. The truth is, however, that the short-lived (15 – 20 years at best) economic gains from hydrocarbon and mineral exploitation will be greatly outweighed by the costs that the permanent damage to the environment will have on the entire region. Note that 95% of the profit by the mining industry will leave the country under the new mining law, while leaving 100% the long-term costs of extraction in the country. Furthermore, the expansion of extractive activities inflicts a disproportionate cost on the inhabitants of these fragile ecosystems, most of which would have 100% of their ancestral land affected (see map below) and their way of life destroyed.

Oil blocks expansion and indigenous territories

There are better alternatives than extractive industries! Stay tuned for Part II: Extractive activities valuation and alternatives. For now, you can stand in solidarity with the plurinational march by signing this petition and spreading the word. If you are in Quito, download this PDF and connect with others on the street and via social networks. If you are there, be strong, the Ghandi way:

Nonviolence is a weapon of the strong" -Mahatma Ghandi

Update

on 2013-07-15 17:24 by The HumanCoral Team

As of November 23, Ecuador has reached $300 million in its Yasuni ITT initiative to leave its oil underground. However, the $3.3 billion required to make it a reality still seems far off. I say "seems" because this sum is relatively insignificant compared to military defense budgets and the paychecks of the wealthiest 1% of the world. In light of the terrifying new math of climate change, These sort of initiatives are not only only economically desirable, they are morally right, and necessary for the survival of our species.

If you would like to tell President Correa to not expand oil exploitation, please sign this petition.

Above: A call from one group of Earthlings to another. Join us! Save our Amazon, save our future.

Silent Evolution: An awe-inspiring underwater sculpture park

The underwater sculpture park by Mexico-based artist Jason deCaires Taylor is a perfect example of an interdisciplinary approach to tackle overarching challenges like climate change (and a fantastic topic to kick off the new HumanCoral website). His sculptures are not only beautiful to look at, rich with meaning, and a source of income for people, but are also designed to serve as a habitat for underwater sea creatures. Hundreds of sculptures of people, and most recently, furniture and even a VW Beetle are designed in such a way to attract the settlement of soft and hard coral polyps, lobsters, and fish; many of which are stressed by climate change, pollution, and overfishing.

Life size 8 ton cement replica of the classic Volkswagon beetle.

Project Pinta: An ecological analog ‘test drive’

Did you know giant tortoises were common on all continents except the Antarctic? Galapagos giant tortoises are a relic of prehistoric times that have formed close bonds with their environment, and like many other tortoises, still play an indispensable role as seed dispersers. The effects of their disappearance are difficult to quantify on mainland. We require a natural laboratory like the Galapagos islands to evidence the ecological impact of their extinction.

Galapagos National Park (GNP), with the support of Galapagos Conservancy and SUNY-ESF, is currently carrying out a pilot project for the ecological restoration of the island Pinta through the introduction of thirty nine adult giant Galapagos tortoises. These will be the first tortoises to set foot on Pinta since Lonesome George (Geochelone abigdoni), the last specimen endemic to Pinta, was removed from the island almost four decades ago. The introduction of “ecological analogues”, or species with a high degree of genetic relatedness with those that once occupied an ecological niche, has rarely been attempted around the world (like for example, the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone Park to control herbivore Populations). This is the first time that it will be tried in the Galapagos islands in hopes to revert some of the negative impacts that humans have had directly or indirectly though the introduction of invasive species.

The Galapagos Islands used to be a world-renowned destiny for whalers, buccaneers, and sailors since the XVIII century, where they could easily catch dozens of tortoises at once to obtain fresh meat that would not spoil during their long journeys. By the end of the XIX century, the exploitation of tortoises intensified to such a degree that tortoise oil was used to light up the streets in Quito at night. Today, 10 of the 14 identified galapagos tortoises still have populations in the wild. In the case of Pinta, we know that the G. abigdoni populations were already so small 100 years ago that they could have already be considered “ecologically extinct” then. Records from the California Adademy of Science from 1906 state that they removed three male tortoises from Pinta. G. abigdoni was considered extinct in the wild since, until Lonesome George was discovered by chance and taken to captivity in 1972.

In 1959, the same year that GNP was established, fishermen introduced three goats to Pinta, and their numbers exploded to over 30,000 in less than 15 years. After arduous efforts from GNP, Pinta was finally declared goat-free in 2003. The eradication campaign eliminated over 40,000 goats on Pinta, which clearcut large part of the island’s vegetation, severely threatening the 176 native plant species and the ecological processes that have sustained local flora and fauna for millions of years. The presence of goats and the absence of tortoises was a fatal combination, as it heavily altered plant communities. For example, the native woody shrubs that goats would prefer not to eat (Castela galapageia and Cryptocarpus pyriformis) have become abnormally abundant. Furthermore, the absence of a large herbivore could result in the demise of other endemic species, especially those that are most shade intolerant. Due to the close interaction between tortoises and Pinta’s vegetation, several experts have advocated for the return of tortoises to Pinta to restore and balance the ecosystem.

Unfortunately, Lonesome George is the last known member of its species (G. abigdoni), and any solution that involves his descendants (to this day nonexistent and with each passing year his reproduction becomes less likely) would take decades to bring about while the island ecosystem continues to degrade without a tortoise population. The most genetically similar tortoises to G. abigdoni are those from Española island (Geochelone hoodensis). A recent study has shed light on the possibility that there may still be G. abigdoni descendants on Volcan Wolf, Isabela Island. Until these tests are finalized, GNP chose to introduce a small population of non-reproductive tortoises - thirty-nine hybrid tortoises that were kept in captivity by the GNP. Their behavior, movements, and impacts were monitored from May to July 2010 after their initial introduction and follow up studies will take place throughout the following years. These tortoises were chosen for their morphology and size. The GNP has the support of Dr. James Gibbs and Elizabeth Hunter from SUNY ESF, who are leading the monitoring project with three main goals:

- Monitor tortoise impacts on island vegetation

- Estimate what is the island’s tortoise carrying capacity with the present plant composition

- Develop a strategy for future releases

The return of tortoises to Pinta, besides an besides an event of great ecologic importance, also has great symbolic value for GNP. Not only are Galapagos tortoises the most emblematic creatures of the “bewitched islands”, but Pinta is the specific island where Lonesome George comes from, perhaps the best known galapago in the world. We hope this project helps us return Pinta to a more pristine state. Projects like these, which help us better understand the complexity of the systems in which we live in and our place within them, may demonstrate our capacity to be a a positive influence on the ecosystem.

Read more about this fascinating project on its official blog: http://retortoisepinta.blogspot.com

Update

on 2012-11-18 16:55 by The HumanCoral Team

On June 24 the symbol of the Galapagos National Park and of conservation worldwide, Lonesome George, passed away. Lonesome George was thought to be the last remaining member of his species, Geochelone abigdoni. However, George might have not been so lonesome after all: scientist have just found 17 hybrid tortoises which can trace ancestry to G. abigdonion the island of Isabella. Five of them are juveniles, suggesting that there may be a live purebred specimen still running around. Yale and the Galapagos Conservancy hope to collect hybrids and any surviving members of both Pinta and Floreana Island species and begin a captive breeding program that would restore both species.